Darkness envelopes capitals worldwide in vacuous black as landmarks ignite in a box office consuming blaze: making plans for August was not a good idea in 1996 – except for Lucasfilm, which was concocting its own significant Shadows…

As heavy drops of Time imbued the parchment of history in omniscient black ink in 1996, they recorded such events as the 30th anniversary of Super Bowl, William Wallace’s victory on the red-carpeted battlefields of the Shrine Auditorium, the cloning of sheep Dolly and Homer’s unwitting killing of Bill Clinton and presidential candidate Bob Dole. Time also skilfully shaped a turning point in the corporate history of Lucasfilm, whose future repercussions were subtly suggested by the tasteful ballet of ink strokes drying into eternity.

At the outset, the Star Wars video relaunch of 1995 was an outstanding success by all means. Approaching 30 million units at ludicrous speed, the sprawling THX-video set had vibrantly re-established the story of a boy, a princess and a universe once again. Thus equipped with lavish measures of popularity, our dear star-travelling heroes, their startling action sequences and abundant mythological and romantic tittle-tattle re-emerged as touchstones of watercooler and schoolyard discussions.

With such promising public response under the wings, the Ranch was understandably bustling with activity. Storyboards of exotic Jedi Knights, the inorganic cityscape of Coruscant and the exploits of a resilient slave, 8 years of age, were briskly piling up. Among them – a particularly intriguing rescue sequence during a daring race on the desert plains of Tatooine, with every pencil stroke echoing weighty words: Powerful Jedi he was… Still, a momentary success and easily the most anticipated film production in the pipeline do not constitute a licence for self-congratulatory idleness.

As the history books of countless corporations reveal, a property must undergo constant development to ensure unquestionable marketability in the future. A cracking video release and a red-hot toy line can only fill so many coffers in a given period of time, for saturation inevitably sets in without remorse, gnawing briskly away on the piers of any product. Lucasfilm had to grow more active.

It was first and foremost licensee Kenner which reliably kept interest in the Saga at fever pitch. While an unlikely development of things, considering that Lucasfilm had successfully restarted the franchise entirely independently, the new Star Wars action figure line achieved two crucial precedents: first, although children were inevitably drawn to Force-ful products due to the cascading sensations triggered by the video re-issue, grown-ups proved essential to astronomic turn over figures, just as Kenner´s Tim Hall had assumed (see Dark Times – LIFM#10 / Pt. 5). The love for Star Wars was still burning in twenty- and thirty-year olds, and these action figures were a perfect opportunity to vent some of their excitement.

Secondly, with their strength replenished, possibly in an as yet unknown part of Broca´s Area, veteran Star Wars aficionados innately remembered all the character names with great ease. Kenner´s decision to start the new line of toys from scratch therefore meant that every new release announcement would be greeted with overwhelming anticipation. The figures had to look authentic and familiar, strangely reminiscent of the times when high school prom felt eons away.

Images of unreleased figures were invariably pirated and posted on the WWW, for what could possibly be of greater importance than a new sculpt of a good ol´ friend? Furthermore, the designs were not solely more technically and hence more artistically advanced – for the sculptors could exert the well-honed craft with much greater abundance with new tools at their disposal – but most crucially, the new action figures were finally vigorously based on Star Wars Saga continuity. One particular case in point was Kenner´s original version of poor, short-lived Greedo, whose nauseatingly green jumpsuit looked unquestionably snazzy in ye goode olde days, yet seemed a somewhat impractical, attention-grabbing fatigue for a bounty hunter. Such flaws occurred to a large degree because designers had then only received headshots of the creatures they were to miniaturize and were thus doomed to second guessing from faces the characters’ actual clothing and size (hence the infamous tall, bluish Snaggletooth boasting tacky silver boots). However, everything had indeed changed for the better in the 1990ies and Kenner received full support from Lucasfilm. The new Greedo was an immediate favourite, what with his original orange jacket and striped trousers.

Such a revisionist design revolution looked gorgeous in general, but to the in-crowd, it was something to wait and hope for on a regular basis. At times, it even seemed as though new films, books and such would be redundant, so popular did the Star Wars toy line turn out to be: Kenner´s previously unreleased Grand Moff Tarkin was an absolute show stopper on the collecting scene of 1996.

A third precedent was Kenner’s ability to unite all existing generations of Star Wars fandom, creating for Lucasfilm a vast movie audience in advance of the first Prequel. Over the 90ies, George Lucas’ companies had produced excellent products for different media, and also different consumer groups, yet never was the world more united than by these terrific toy figures. Kenner was the perfect catalyst for Lucasfilm at the perfect time.

Observers may have found it bewildering that Lucasfilm had as yet stayed clear of a more expansive, co-ordinated project. Regardless of brisk sales, the various bouts of Star Wars entertainment were conspicuously isolated in nature, lacking cross-cultural impact despite being released at a time when an exciting environment of integrated content distribution platforms was growing fast.

As case in point was LucasArts’ Rebel Assault II, which certainly addressed the need for more integral involvement in the Star Wars universe rather handsomely, especially with a special appearance of Vader in good choking mood. Yet not only was it limited in terms of general market penetration by its very nature as a computer game, but with a plot in which yet another Imperial weapon was poised to be blown into a million pieces, the successful multimedia experience was arguably too far removed from our beloved heroes. People are certainly not quite as emotionally connected to an abundance of space debris. So with none of the trusted band of Luke, Leia and Han, as well as Chewbacca, Lando and the droids in tow, Rebel Assault II, though arguably a bright star from a certain point of view, was an isolated affair.

It was after all a time of change when the momentous evolution of technology had expelled the entertainment industry from the comfortable 70ies and 80ies to the nauseating multitude of revenue streams of the 1990ies. No longer did a motion picture reign as a singularly vital entertainment property. Films had been coerced into ceding valuable ground to ancillary products. Novels, computer games, videos and indeed then still fledgling online content challenged the popularity and – most importantly – the commercial viability of film production.

Lucasfilm reacted with determination and revved up their operations exponentially by starting a project that would set in motion franchise management practises that are in effect to this very day.

As early as 1994 Lou Aronica of Bantam had suggested to Lucasfilm publishing director Lucy Autrey Wilson that their companies should launch a combined multimedia project, ‘with one story line going through different product categories’. ‘[…]1996 was the perfect year, since there were no major Star Wars projects, such as a movie launch’, explained Wilson (p8, The Secrets of Shadows of the Empire, Mark Cotta Vaz, 1996). The multimedia event should furthermore depart noticeably from Zahn’s sequel novels or Anderson’s Tales of the Jedi and directly extend the continuity of the OT from within. Original plans to place the bridge story between ANH and TESB were quickly scrapped after LucasArts graphic designer Jon Knoles – the man responsible, apart from a great many other things, for the fine pests of TIEs and Dark Troopers that made your computer gaming life so entertainingly miserable – sent a convincing memo to Lucasfilm: ‘[S]etting [the story] in between the second and third films […] provided more cliff-hanging [and] dramatic possibilities’. Lucasfilm’s Howard Roffman elaborates: ‘It’s in the midst of the Rebellion, and Luke Skywalker, who’s very vulnerable because he hasn’t finished his Jedi training, is now diverted because he wants to rescue Han Solo, who’s encased in carbonite and in the biggest peril he’s ever been in. On the Imperial front, you have the Emperor embarking on his plans to build a second Death Star while Vader is obsessed with finding his son and turning him to the dark side’ (p 14, The Secrets of Shadows of the Empire, Mark Cotta Vaz, 1996 ).

Such a promising premise in hand, Lucasfilm developed an intense, multilayered story of subterfuge at the highest level of the Empire, building on fissures in the relationship between Palpatine and Vader that TESB had hinted at (and which would be further elaborated in the 2004 DVD set). The narrative would begin literally as TESB’s plot is quickening and end mere moments before the galaxy’s most durable droids would head for Jabba The Hutt’s lair at the beginning of ROTJ.

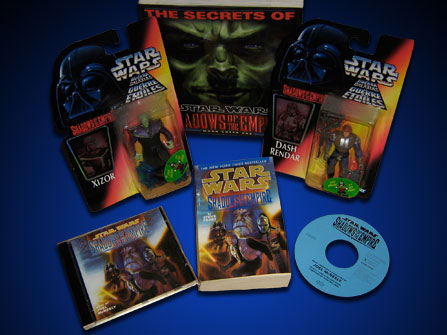

The story introduced to the Star Wars universe Black Sun, the mysterious and immanently dangerous organisation led by Xizor, a prince from the planet Falleen. He wishes to manipulate Vader into falling out of the Emperor´s favour by framing the Dark Lord in an assassination of Luke Skywalker before he can be handed over to Palpatine.

The crime lord´s devious plan inevitably interferes with the Rebel´s desperate struggle to rescue Han from the clutches of Boba Fett, who has his own score to settle with his fierce competitor IG-88.

Thus understandably overwhelmed, Leia recruits the services of ersatz-Han Solo and merc for hire, Dash Rendar and his loyal robot Leebo, who have possibly the second-biggest pile of junk in the galaxy at their disposal, the space freighter Outrider.

Darth Vader would meanwhile scour the stars in search of young Skywalker, yet uncommonly perturbed by Xizor´s smart relationship with the Emperor. Although quite a rare occasion, Vader has every reason to be greatly concerned, for he was responsible for killing Xizor´s family during the “purification” of Falleen after a weapon experiment had gone horribly awry. Xizor was not simply an intergalactic careerist, but ruthless predator craving for Vader’s heart.

The portentous title of this intriguing epic: Shadows of the Empire.

As with George Lucas´ original draft for “The Star Wars”, the plot outline possessed a most daunting scale. Every single element seemed indispensable, so exciting were the tale’s overlapping conflicts and relationships. Much rather than spreading out the narrative to three volumes as Lucas had previously done with the OT, Lucasfilm put into effect the vision sketched by Bantam’s Aronica, a vision so grand and fateful, it would not merely evolve into a truly multi-medial product but the very blueprint for the future of the Star Wars franchise.

Author Steve Perry, the man behind the popular Matador series, wrote a novel that explored the events leading up to C3-PO’s and R2-D2’s arrival at Jabba’s palace in ROTJ.

Dark Horse comics took on responsibilities to explore Boba Fett’s involvement. While the fearsome bounty hunter made only a very limited appearance in the novel proper, the comic book series devised by legendary John Wagner elaborated on Fett’s struggle with the resilient IG-88, who intends to relieve him of his valuable charge, Captain Solo.

Lucasfilm’s commitment to Shadows of the Empire truly rivalled motion picture projects, a fact underlined by Robert Townson, vice-president of soundtrack label Varése Sarabande, who had long harboured the dream of Star Wars music written for prose fiction. With its lush narrative palette, draped in the thick textures of charismatic characters waiting to be probed by inquisitive movements of music, Shadows was an irresistible opportunity. Townson had long wanted to reap the greatest benefit from being relieved of the burdensome chores of motion picture scoring, which ever so often is painfully subjugated by the film’s editing process: ‘[T]he most important rule was just to write great music[…]. In a film everything is put before [an audience], while in a book [readers] are being asked to visualize characters and scenes for themselves. This sound track gives them another piece of the puzzle to take an extra step into this world.’ Joel McNeely, who had previously cut his teeth on adventure for Lucasfilm’s Young Indy series was ideal for realising Townson’s dream: ‘[M]y initial impression of Xizor was – ethnic. Something Middle Eastern, slightly primitive in style, but with a real seductive side, a lot of drums. [A] palette of musical colors and I work from that, refining until a real clear concept and theme develop. [Without] the motion picture considerations to deal with, I could really make the music uniquely original to me, both thematically and stylistically’ (p258-61, The Secrets of Shadows of the Empire, Mark Cotta Vaz, 1996 ).

To enrich the striking narrative further, LucasArts was charged with developing an appropriate video game that put players exclusively in Rendar’s position. The designers had something rather special in mind, for they wanted to involve players in ways unseen in electronic gaming. It needed to be an amped-up, real-time Rebel Assault sort of game.

TO BE CONTINUED…