It had already been five years since ROTJ and still not a single light saber on a new movie poster. Yet underneath the frustration, a potent potion was brewing…

Howard Roffman, head of Lucasfilm Licensing, once pointed out how all franchises would evolve in specific cycles, with the original consumer generation eventually growing out of a particular craze and the franchise concerned slowly fading away. Therefore, he argued, Lucasfilm would never push a particular item onto the market out of context, for otherwise they might waste a perfectly good product.

One such great product certainly was the white sweater bearing that bold ANH 10th anniversary logo. Alongside Drew Struzan’s remarkable commemorative poster, that piece of clothing was an awesome reminder of the innocent experience of watching Obi-Wan disappear, Luke get a face lift and the Emperor draining all power from the East coast.

Yet by 1988 the anniversary celebrations had long since subsided as the world prepared for immanent Batmania or the return of a whip-cracking archeologist. It also happened to be the year that accelerated Tom Hanks’ career in a BIG way. From a different perspective the situation still did not seem as dire.

A quick glance back at 1983 reveals that ROTJ had finally allowed George Lucas to create a sprawling entertainment company operating entirely independently. Three subsidiaries in particular rose to immediate fame, namely ILM, THX and Lucasfilm Games. They would create an environment over the next few years where Star Wars could continue to germinate in the minds of the people.

In between 1980 and 1990, ILM created a range of jaw-dropping effects for films such as Dragonslayer, E.T., the second Indy film, the Star Trek features, Young Sherlock Holmes, Innerspace or Die Hard 2.

One particular project was paramount to maintaining close ties with the rapidly changing face of the movie-going public: Bob Zemeckis, director of blockbusters Romancing the Stone (1984) and Back to the Future (1985) gave the world Who Framed Roger Rabbit in 1988, a roaring detective yarn set in a fantastic exaggeration of show business where humans and cartoon characters – or “Toons” – would live in (occasionally not-so) happy coexistence. The integration of cel animation in live action footage – and vice versa – was a difficult task Zemeckis charged none other than ILM with.

![]() Ken Ralston, who had become the director’s regular effects supervisor with Back to the Future (and continues to be to this day even after having left ILM), engineered seamless composites. Key to the perfectly believable sensation of “Toons” interacting with the human world was not only compositing the various elements properly but indeed devising extra-clever mechnical contraptions and in camera effects so that animators could animate “around” the live action plates. The scenes where, for instance, actor Bob Hoskin’s private eye struggles with Roger Rabbit in a sink and the unlikely duo’s desperate attempt at ridding themselves of their handcuffs have become world famous. Ken Ralston and ILM would receive an Academy Award for their execeptional work. Yet there was another and rather priceless gain for George Lucas’ troupe.

Ken Ralston, who had become the director’s regular effects supervisor with Back to the Future (and continues to be to this day even after having left ILM), engineered seamless composites. Key to the perfectly believable sensation of “Toons” interacting with the human world was not only compositing the various elements properly but indeed devising extra-clever mechnical contraptions and in camera effects so that animators could animate “around” the live action plates. The scenes where, for instance, actor Bob Hoskin’s private eye struggles with Roger Rabbit in a sink and the unlikely duo’s desperate attempt at ridding themselves of their handcuffs have become world famous. Ken Ralston and ILM would receive an Academy Award for their execeptional work. Yet there was another and rather priceless gain for George Lucas’ troupe.

Since Who Framed Roger Rabbit? was a family picture featuring a most intrguing premise, adults and children alike were absolutely restless to learn how filmmakers managed to bring Roger and the other “Toons” to life in the reel world. An exciting, made-for-TV behind the scenes featurette accompanied the film’s release and was a ratings winner worldwide. Consequently, with many a reference made to ILM, a new generation became intrigued by Lucas’ company without there being any new Star Wars motion picture material.

In the same vein, hundreds of theaters would be THX certified around the world, hence literally ushering in millions of movie goers to a very amazing film experience via the by-now celebrated THX intros, which, until 2005, would squarely feature the Lucasfilm brand name.

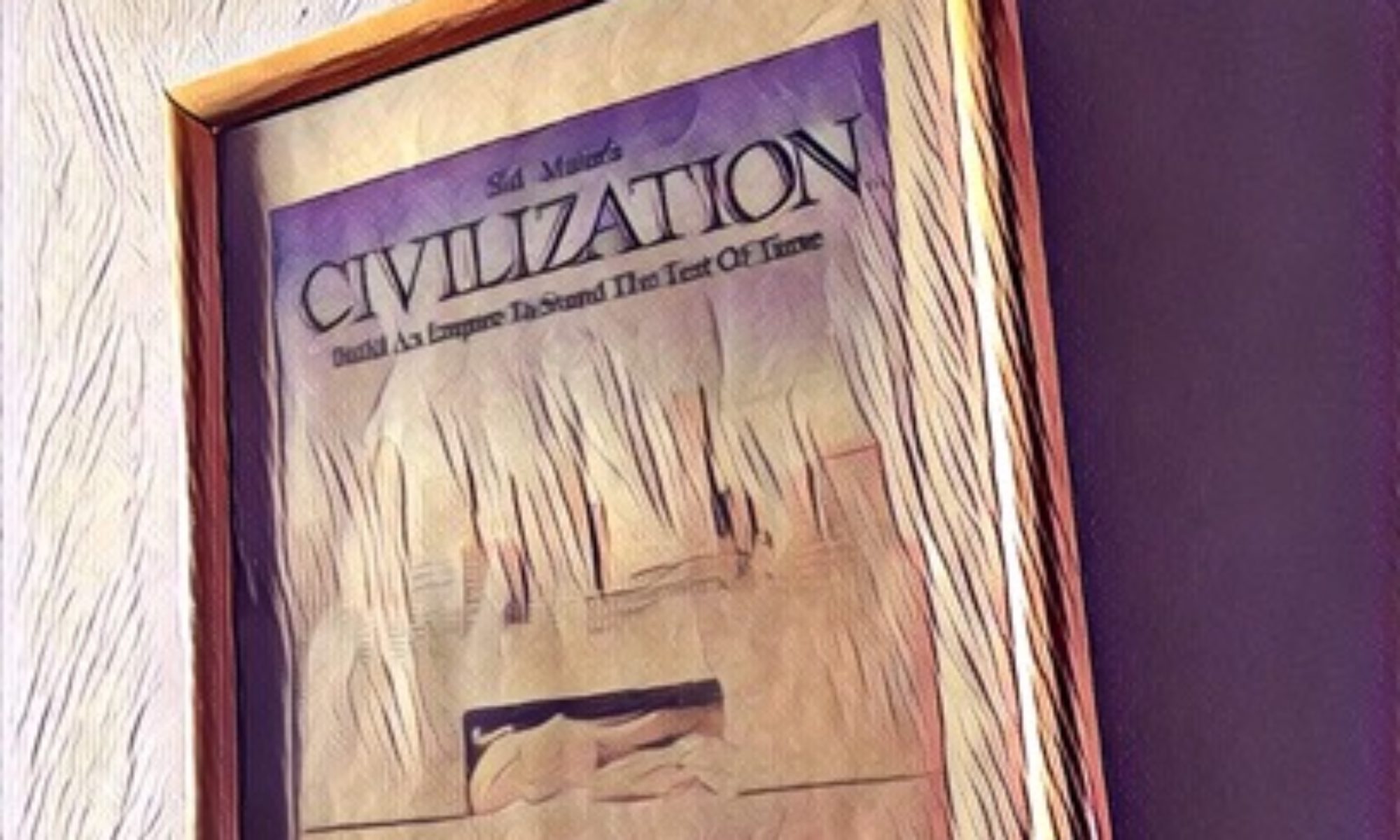

Lucasfilm Games (today’s LucasArts) made itself a name for state-of-the-art, narrative based computer games. After early releases thrilled gamers with remarkable fractals graphics, Ron Gilbert’s and David Fox’s Maniac Mansion single handedly inaugurated the age of point-and-click adventuring.

Together, the prolific output from Lucasfilm companies ensured that the world would be constantly, however indirectly or fleetingly, reminded of Star Wars. Maniac Mansion in particular not only featured an X-Wing in Ed’s room, but also a Star Wars film poster in the mansion’s arcade hall, amongst other essential Force-related references.

1988 may have seen the release of DOMARK’s The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi arcade conversions for home computers, as well as Star Wars for the NES, but it also harboured intriguing rumours: ILM had cancelled all production to channel all resources to a top-secret project. According to certain film magazines, this could only mean that a new batch of Star Wars films was in the works.

Rumour mills aside, neither did an aged Luke Skywalker ponder the essence of the Force, nor did little Anakin cry “Yippee” on the big screen just yet. But it was virtually impossible not to keep this peculiar saga in mind, not with George Lucas’ crew toiling away at highly regarded products. The context required for a franchise to come to fruition was indeed very much alive.